Apparatus and methodology for smart trainer homologation analysis. (View Article)

I led the development of the cycling testing rig described in this paper, which is used for assessing cycling home smart trainers.

Engineering Ph.D. Candidate | Seeking R&D Roles – Graduating 2025

For the central project in my graduate research at Purdue University, I led the design and development of a cycling test rig. Initiated in 2020 under the guidance of my Primary Investigator (PI), Dr. Mansson, this project addresses the growing popularity of virtual cycling and the critical need for regulated power measurement in cycling smart trainers. The rig enables rigorous evaluation of smart trainer accuracy, a necessity for fair competition in virtual cycling. I also extended this project to use for studies in cycling chain lubrication, by using the testing rig to perform precise assessment of cycling drivetrain lubricant efficiency over time.

My contributions included overseeing the entire lifecycle of the project, from initial conception and design to assembly, electrical integration, and software development. The testing rig has been instrumental in collaborative testing with the International Cycling Union (UCI) to test and evaluate smart trainers for world competition homologation. All relevant publications and media mentions are detailed below.

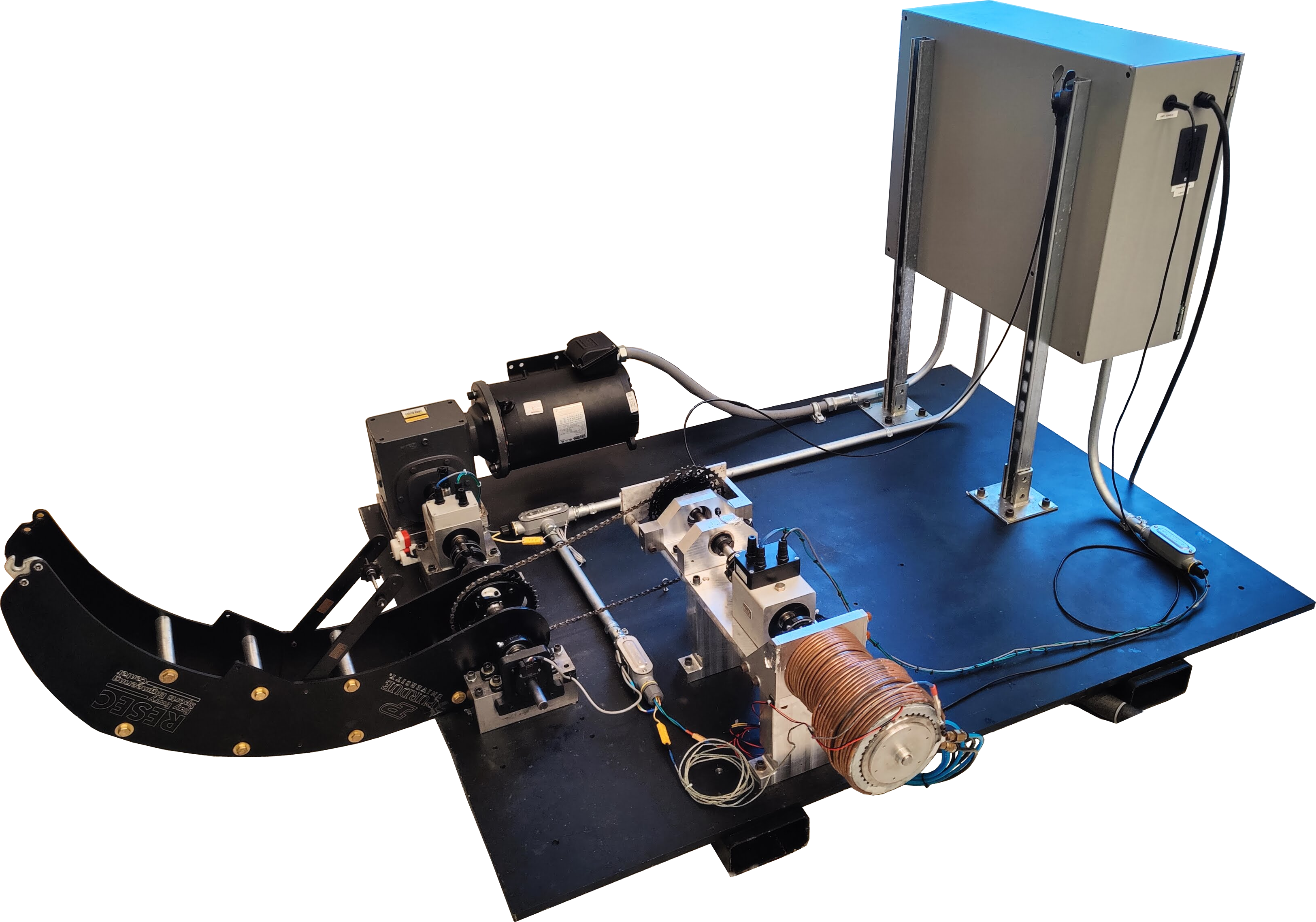

Figure 1: The Cycling Test Rig

Figure 2: Adjusting a Smart Trainer Attachment

The testing rig serves two primary purposes and are performed in two configurations: 1) to evaluate the accuracy and quality of cycling smart trainers ("smart trainer configuration"), and 2) to assess the efficiency of cycling drivetrains, particularly focusing on lubricant performance ("drivetrain configuration"). The main components and running software are the same, with the difference being switching out the tested object being a smart trainer or a drivetrain, detailed below.

I spearheaded the design and assembly of the testing rig, incorporating feedback from fellow graduate researchers such as Justin Miller (avid cyclist) and Diana Heflin. Key components (Figure 3) include: (A) AC motor, (B) gear reducer, (C) torque transducer, (D) rotary encoder, (E) smart trainer/drivetrain, (F) electrical box, and (G) back side view. Using SolidWorks, I managed the detailed design and oversaw the physical construction in the lab.

Figure 3: Test Rig - Smart Trainer Configuration

Figure 4: Test Rig Control Program Interface

I also led the electrical design and integration, working with a licensed electrician to ensure safety and compliance, and personally assembled the electrical system. The control and analysis software, crucial for data acquisition and real-time analysis, was developed in Python using PyQt5 for the graphical user interface. I was primarily responsible for this software, with later support and development from Patrick Cavanaugh. The user interface is shown in Fig. 4.

Smart trainers can be used for virtual races, where competitors around the world race synchronously at home on their own smart trainers through an online platform. The smart trainer testing configuration can be seen in Figs. 1-3 and 5. In this configuration, the drive system inputs power into the attached smart trainer. The control program reads the power reported from the smart trainer and the power reported from our testing system. By knowing the difference between these two power values, we can calculate the accuracy of the smart trainer. This configuration has been presented at multiple conferences and media appearances detailed below, including RALLY Innovation 2023, as shown in Fig. 5.

This project has been done in coordination with the International Cycling Union (UCI), and we have been in discussions with them to "homologate" the smart trainers to help level the playing field by testing these trainers to make sure all models used in high-level virtual cycling competitions read the same power values.

Figure 5: Test Rig at RALLY 2023

The setup for drivetrain efficiency testing was adapted from the smart trainer configuration. The smart trainer was replaced with a standard cassette and derailleur (Fig. 6, F), along with a second torque transducer (Fig. 6, E) and a controllable electromagnetic brake (Fig. 6, D). This setup allows precise measurement of power input to the drivetrain and power output after being transmitted through the drivetrain, enabling calculation of drivetrain efficiency.

Fig. 7 shows a picture of the test rig in the drivetrain testing configuration. Within the drivetrain, we have focused on the effects of chain lubrication on efficiency. We have developed a procedure to test these chains over a wide array of conditions, from 200-800 W and 60-120 RPM (cadence). The efficiency is tested, then the chain is run for an hour, and then the efficiency is tested again. In this way, we can see how the efficiency of the lubricant changes with respect to time, which has been missing from many prior lubricant testing regimes. This setup has allowed us to gain valuable insights into the performance and degradation of different cycling lubricants over time. There are two upcoming publications detailing the work on this project.

Figure 6: Test Rig - Drivetrain Testing Configuration

Figure 7: Drivetrain Testing Setup

The following publications and media coverage highlight the cycling test rig and its applications in smart trainer homologation and bicycle chain lubricant analysis.

The following publications and patents showcase my contributions:

I led the development of the cycling testing rig described in this paper, which is used for assessing cycling home smart trainers.

I used the cycling test rig to collect data showing the change in bicycle drivetrain efficiency over time as the lubricant degrades.

I served as the main design engineer on the design and manufacturing of the cycling testing rig. This rig is used for my work on smart trainers and cycling drivetrain lubrication research.

I presented the initial design of the cycling testing rig used for cycling smart trainer analysis.

I contributed to developing the initial data analysis methodology for the cycling testing rig.

Selected media appearances showcasing my work:

This article details our work at Purdue's Ray Ewry Sports Engineering Center (RESEC) in developing a homologation system for virtual cycling to ensure fair competition. My efforts contributed to paving the way for virtual cycling to potentially become a recognized Olympic sport.

This article discusses the UCI's upcoming smart trainer standardization initiative and the implications of this project for the future of virtual cycling and its potential integration into major sporting events.

I and other members of the Ray Ewry Sports Engineering Center research team were interviewed about our work in developing the UCI's Smart Trainer Standardization Program, and its impact on the future of cycling esports and the potential for Olympic inclusion.

This news story highlights my contributions to the Purdue team working to standardize smart trainers for virtual cycling, with the goal of ensuring fair competition as the sport potentially debuts in the Olympics.